Introduction

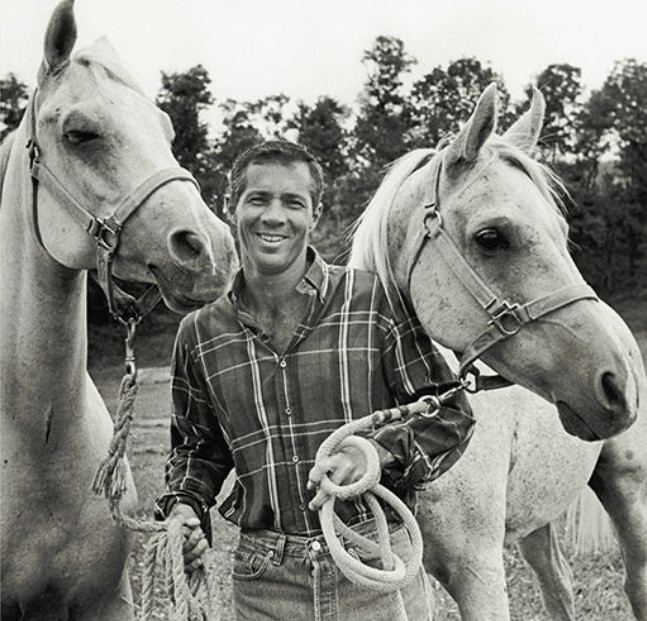

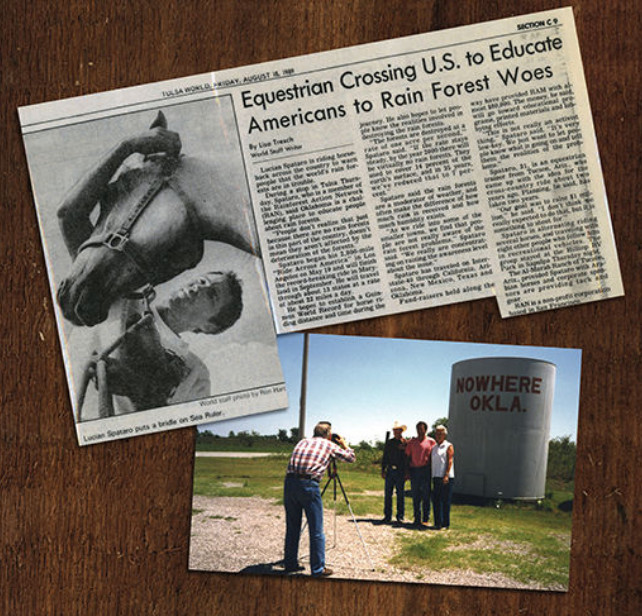

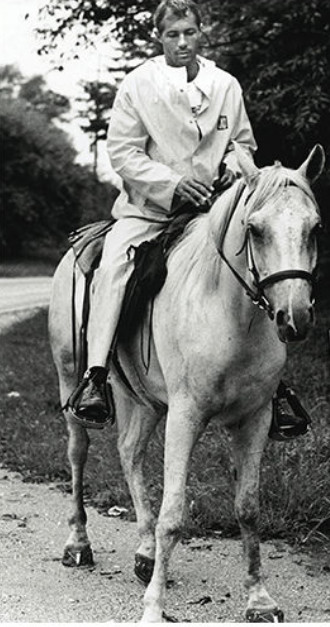

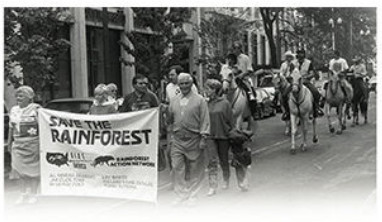

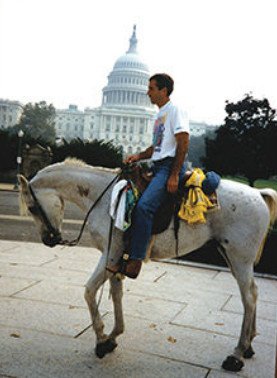

It was a journey to remember, a record breaking quest to not only cross the country on horseback, but to raise awareness about the environmental challenges our planet faced then and still faces today. Starting in Los Angeles, CA, Lucian Spataro, with the support of his devoted team, rode on horseback coast to coast, completing the remarkable trek in Chesapeake Bay, Maryland 150 days later. In doing so, Spataro rode through the heat of the western desert, and the humidity and driving rains of the Midwest, arriving in the East in time to take in the splendid fall foliage. In the process, the record for a cross-country ride not only fell, but was cut in half. It’s an extraordinary story of endurance and dedication to a cause we should all care about.

It was a journey to remember, a record breaking quest to not only cross the country on horseback, but to raise awareness about the environmental challenges our planet faced then and still faces today. Starting in Los Angeles, CA, Lucian Spataro, with the support of his devoted team, rode on horseback coast to coast, completing the remarkable trek in Chesapeake Bay, Maryland 150 days later. In doing so, Spataro rode through the heat of the western desert, and the humidity and driving rains of the Midwest, arriving in the East in time to take in the splendid fall foliage. In the process, the record for a cross-country ride not only fell, but was cut in half. It’s an extraordinary story of endurance and dedication to a cause we should all care about.

California

9:30 AM and I was sitting on my white horse, Willy, at the corner of Taft and Glassell in Los Angeles with Anaheim Stadium off to my left. I was waiting to cross eight lanes of rush-hour traffic, the exhaust stinging my eyes. Beside me was a man with a shopping cart full of junk, a young lady in a bright yellow running suit jogging in place, and an older man in a business suit, with a brief case. I let the reins drop a bit and began to peruse my street map. I was in no hurry – I still have 3000 miles to go.

9:30 AM and I was sitting on my white horse, Willy, at the corner of Taft and Glassell in Los Angeles with Anaheim Stadium off to my left. I was waiting to cross eight lanes of rush-hour traffic, the exhaust stinging my eyes. Beside me was a man with a shopping cart full of junk, a young lady in a bright yellow running suit jogging in place, and an older man in a business suit, with a brief case. I let the reins drop a bit and began to peruse my street map. I was in no hurry – I still have 3000 miles to go.

We must have made quite a sight for those Friday morning commuters. I was wearing running tights, Nike running shoes, a baseball cap and a small backpack. Willy had two of my shirts hanging off each side of the saddle, a water canteen and lead rope tied to the back of the saddle. I’d already noticed that when the light changes, these LA drivers didn’t look left and right to be sure the pedestrian lane was clear before they hit the gas peddle.

When the crossing light went green, the others were off in a flash. It took me a moment to get moving. I tried trotting to make up time, but with steel shoes on, Willy had a slippery time of it. Better to take it slow, especially with all of the noise and commotion. Even if the drivers did honk their horns, gun their engines and stare. Welcome to The Long Ride.

Arizona

This was one hot stretch. I consumed about 3 gallons of water per day and didn’t even need to stop to relieve myself. We were so thirsty, we thought about water all the time. This element that we take for granted on a daily basis suddenly became a central preoccupation, and the sensation of thirst became a very familiar feeling.

One of the hardest tasks was to remain alert. The rhythm of the cars whooshing by, together with the steady rocking of our gait, had a hypnotic effect on us. We got drowsy and Willy and I both fell into a trance. We began to daydream often and the cars passing by played tricks on our minds.

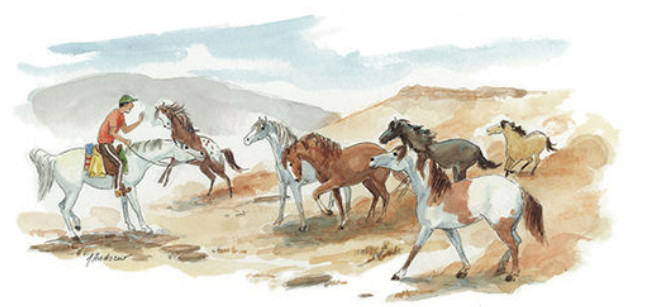

. . . out of nowhere, like a mirage from the heat, I saw a dust storm coming up off the ridge. But no, it was a group of horses, and they were running full tilt right at us. Willy was prancing in circles and I was doing everything I could do to hold him. I was determined to stand our ground because I knew we would tire too easily in an all-out sprint. It was late in the day and we were 18 miles into a 24 mile trek, temperature 104. If we stood our ground, we might bluff them. Willy was all over the place as they galloped our way, and I had to keep him prancing in circles to control him.

. . . out of nowhere, like a mirage from the heat, I saw a dust storm coming up off the ridge. But no, it was a group of horses, and they were running full tilt right at us. Willy was prancing in circles and I was doing everything I could do to hold him. I was determined to stand our ground because I knew we would tire too easily in an all-out sprint. It was late in the day and we were 18 miles into a 24 mile trek, temperature 104. If we stood our ground, we might bluff them. Willy was all over the place as they galloped our way, and I had to keep him prancing in circles to control him.

Just as they were closing in on us, Willy suddenly stopped prancing, turned to face the oncoming horses, planted his feet wide apart and stood very still and steady, nostrils flaring.

The lead horse, who was red and had a screaming whinny, stopped and snorted. The other horses milled behind. Bluffing confidence, I clicked a knee into Willy to square him off to the lead red horse. We were about 20 feet apart, close enough for the horse to reel and kick us. The red horse was flaring his nostrils and weaving his head up and down, snaking it around as if trying to get a sniff on us. Then he reared up pawing the air. Willy and I had stood our ground . . .

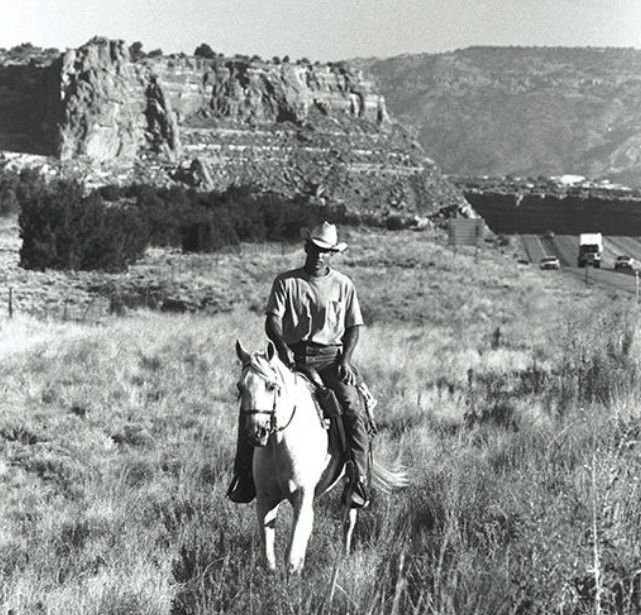

New Mexico

Just east of Gallup, New Mexico, we came to a small row of houses and farms. It was early on a Monday morning, so I was really amazed when around the next corner I heard a minister preaching in an open air church. As we rounded the bend in the road, the minister said, “These kids nowadays have no common sense, no horse sense.” Just alignleftas he said the words “horse sense” Willy let out a shrill whinny. Willy is not the most vocal of horses. In fact, that was the only time I ever heard him so much as nicker, other than maybe a snort of recognition at one of my other horses, March Along. So something special was happening here.

Just east of Gallup, New Mexico, we came to a small row of houses and farms. It was early on a Monday morning, so I was really amazed when around the next corner I heard a minister preaching in an open air church. As we rounded the bend in the road, the minister said, “These kids nowadays have no common sense, no horse sense.” Just alignleftas he said the words “horse sense” Willy let out a shrill whinny. Willy is not the most vocal of horses. In fact, that was the only time I ever heard him so much as nicker, other than maybe a snort of recognition at one of my other horses, March Along. So something special was happening here.

The sermon stopped and the whole congregation turned around and stared at us, passing only about 75 feet away on the road. I couldn’t help myself. I was laughing hysterically and pointing at Willy and shrugging my shoulders as if to say “he’s got a mind of his own.” I have to say his timing was impeccable. There wasn’t another horse in sight to make him whinny like that. He must have overheard the preacher and simply taken exception to that particular piece of the sermon. Willy was excellent company.

Texas

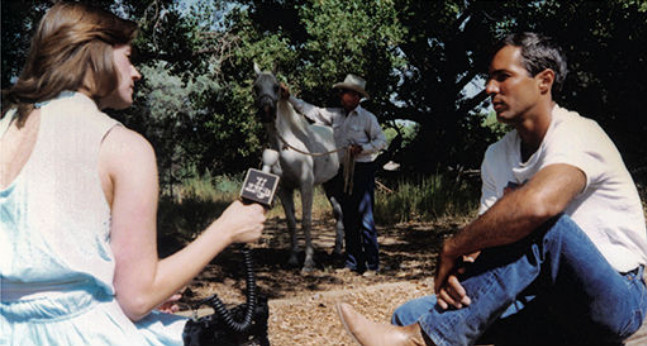

On day sixty-seven, July 24th, we hit Amarillo, Texas. A film crew met us in the early morning to film Willy and me doing our thing for the local evening news. The reporter asked me several questions about the ride and our purpose. At the end of the interview he asked the most important question: “What impact does deforestation in the rainforest have on Amarillo, Texas, and this area?”

On day sixty-seven, July 24th, we hit Amarillo, Texas. A film crew met us in the early morning to film Willy and me doing our thing for the local evening news. The reporter asked me several questions about the ride and our purpose. At the end of the interview he asked the most important question: “What impact does deforestation in the rainforest have on Amarillo, Texas, and this area?”

That part of Texas is known for farming and ranching, which of course, depends on consistent weather conditions. People in the area need rain and an appropriate climate in which to grow crops and raise cattle. I explained that “deforestation and loss of rainforest impacts the climatic conditions all over the globe, including the panhandle of Texas, the Midwest and other areas of the United States.” It impacts the pollinators that pollinate the crops in this region. Many of these pollinators migrate to the rainforest to winter over and then return to Texas in the spring. We need pollinators to grow crops.

Talking about the interconnectedness of our global environment made our message strike home.

Oklahoma

I call Oklahoma “the calm before the storm” because some of our toughest times were yet to come. The Texas panhandle and Interstate 40 were behind us. Now our plan was to cut through Oklahoma in a straight line on secondary roads, then north again along Old Route 66 up to Joplin, Missouri. Along the Oklahoma stretch, we did a lot of night riding. Both the horses and I liked the cool breezes and low traffic.

I call Oklahoma “the calm before the storm” because some of our toughest times were yet to come. The Texas panhandle and Interstate 40 were behind us. Now our plan was to cut through Oklahoma in a straight line on secondary roads, then north again along Old Route 66 up to Joplin, Missouri. Along the Oklahoma stretch, we did a lot of night riding. Both the horses and I liked the cool breezes and low traffic.

Bridges were always a challenge to contend with. As we rode up to the bridge on the North Fork of the Red River, it looked a little longer than most of the interstate bridges we had crossed thus far. This concerned me because it meant that we were exposed for a longer period of time to the trucks and cars passing within two to three feet of us at high speeds. We were riding with traffic, which meant these vehicles would come up behind us very quickly and very close. There was no room for error or for indecision. It was very hard to maneuver or to turn around if need be, so once we were on the bridge, our best bet was to keep moving forward.

The sun was just coming up, and it was still a little dark out. Maybe we had become too accustomed to these interstate bridges. Or maybe I was too preoccupied with the upcoming rest stop, because without thinking, I rode into a very dangerous situation …

Missouri

We had all been on the road now for more than three months. The close quarters and long hours were beginning to take their toll on the whole team, with the exception of the horses. The adrenaline we’d felt at the start had dwindled away, and we’d begun to realize how far we still had to go.

The farther east we rode, the harder it was to complete a day’s ride. Everyone wanted to stop and talk. We knew that we had to talk about the rainforest at every opportunity, but we also had to make mileage. Then there was the rain. It came down in sheets so thick sometimes we couldn’t see 20 feet in front of us.

The farther east we rode, the harder it was to complete a day’s ride. Everyone wanted to stop and talk. We knew that we had to talk about the rainforest at every opportunity, but we also had to make mileage. Then there was the rain. It came down in sheets so thick sometimes we couldn’t see 20 feet in front of us.

My journal that day contained three comments.

Bazy Tankersley, the owner of A1-Marah Arabians, told me before we left, “In this kind of event, to finish is to win.”

Immediately after that, I wrote: “Nothing of any real significance was ever accomplished that did not require extreme sacrifice.”

Finally I wrote: “if number one and number two are true, then keep it together, whatever it takes.”

Illinois

We made it to the Mississippi River on September 9th, crossed at a town called Chester, and were then in Illinois. The farther we rode, the more meticulous I became about planning and confirming every detail of the route. We wanted to be sure we were choosing the straightest, shortest, and safest route possible.

We made it to the Mississippi River on September 9th, crossed at a town called Chester, and were then in Illinois. The farther we rode, the more meticulous I became about planning and confirming every detail of the route. We wanted to be sure we were choosing the straightest, shortest, and safest route possible.

Some days we spent as much time scouting and talking to local residents as we did riding. Some scouting trips brought us in as late as midnight; then we needed to prepare for a 4:00 or 5:00 AM wake-up call. It was raining every day now.

On September 11th, despite the rain, I covered 38.4 miles using both horses. We were going to try this extra distance every fourth day. Joyce wrote in her journal. “At this pace we will be in D.C. in no time flat.” She mentioned the date, October 15th. Not exactly (no time flat) when you’re in the saddle.

Indiana

As we rode down a lonely rural road, I nodded off and missed a turn that I needed to take toward the Wabash River and the Indiana border. Brad had left us about an hour’s ride from the bridge and was going to meet us there as we crossed into Indiana. When we didn’t arrive, he backtracked until he finally found us heading north up Highway 1.

As we rode down a lonely rural road, I nodded off and missed a turn that I needed to take toward the Wabash River and the Indiana border. Brad had left us about an hour’s ride from the bridge and was going to meet us there as we crossed into Indiana. When we didn’t arrive, he backtracked until he finally found us heading north up Highway 1.

He pulled up alongside us and said matter-of-factly: “How is the ride going today?” “Fine,” I said, “Only thing is, I thought I should have crossed the Wabash by now, maybe it’s up around the next corner.”

“Yeah maybe if you’re riding around the world, because that is the only way you are going to reach the Wabash by riding in this direction.” Brad said.

I felt miserable. It was hard enough riding across country without getting lost and adding unnecessary miles onto an already exhaustingly long trip. Anyway, September 13, was the day we crossed into Indiana.

Kentucky

By now our trailer was experiencing some serious technical difficulties. Neither the air conditioner nor the heater was working. We did not discover the air- conditioning malfunction until we were in Oklahoma, so it got hot in that trailer. Because the heater also did not work, I would sometimes have to turn on all of the gas burners to knock the chill off.

By now our trailer was experiencing some serious technical difficulties. Neither the air conditioner nor the heater was working. We did not discover the air- conditioning malfunction until we were in Oklahoma, so it got hot in that trailer. Because the heater also did not work, I would sometimes have to turn on all of the gas burners to knock the chill off.

I lived in the front of the trailer and the horses lived in the back. I was the only one on the team who could tolerate eating or even simply sitting in there. I had become accustomed to the smell. Most of the clothes I had on the ride still smell like horse manure. It was really bad in the West and Midwest with the heat, and only got worse with the humidity and rain as we traveled east.

During this stretch, we were encouraged to hear CNN had picked up the ride and did two Earth Matters segments on our event. We also had heard that Willard Scott, the weather man on Good Morning America, was interested in our ride and might be able to meet us on the road to telecast a weather report. When you’re goal is to raise awareness, making the news is always good news.

Ohio

My father worked hard setting up different fund-raisers and speaking engagements in Athens, Ohio, my hometown. As I rode through my Athens, the environment was very much in the news, as local activists and concerned citizens were fighting to block the dumping of garbage from New York State in Athens County. There were numerous articles and extensive media coverage about the issue. So we were right on time with our message.

My father worked hard setting up different fund-raisers and speaking engagements in Athens, Ohio, my hometown. As I rode through my Athens, the environment was very much in the news, as local activists and concerned citizens were fighting to block the dumping of garbage from New York State in Athens County. There were numerous articles and extensive media coverage about the issue. So we were right on time with our message.

My father was supportive throughout this endeavor, before and during the ride. I had spoken to him off and on during the planning stages and we discussed the trade-offs of undertaking an effort like this, the personal and economic sacrifices involved.

His comment was: “If you are going to do it, go all the way.” He even promised to buy me dinner at Tucson’s most exclusive restaurant, the Tack Room, when I finished the ride. Come to think of it, he still owes me that dinner.

West Virginia

On September 19th, I rode 27 miles in the rain and crossed the Ohio River at Parkersburg, West Virginia.

On September 19th, I rode 27 miles in the rain and crossed the Ohio River at Parkersburg, West Virginia.

Fall had descended upon the Appalachian Mountains and the trees were beginning to change color. The sassafras, apple, and paw paw, the cool clear air and cool clean water stimulated all my senses–touch, smell, taste, sight, hearing. Everything was in razor- sharp focus.

On October 5th I rode through Grafton and actually completed my ride that day just beyond the Four Corners restaurant. Two months before, a young lady named Claudia Von Ostwalden and her horse, Max, were traveling west along this same stretch when they were struck by a truck. Claudia was uninjured, but the horse could not go on. This horse and rider team was attempting to set a record by crossing the United States on horseback.

I found out later that the young lady was, in fact, trying to race us across the United States. From what I understand, she had left the East Coast soon after we left the West Coast. I estimated by her pace that she rode 350 miles during the same time period we covered 1100 miles.

Virginia

Riding down highway 50 from Clarksburg to Virginia and on into Washington D.C. was a trip I will not soon forget. As we rode at the break of day, we could see mist rising up from the many rivers and streams along the route. I saw wildlife at every turn.

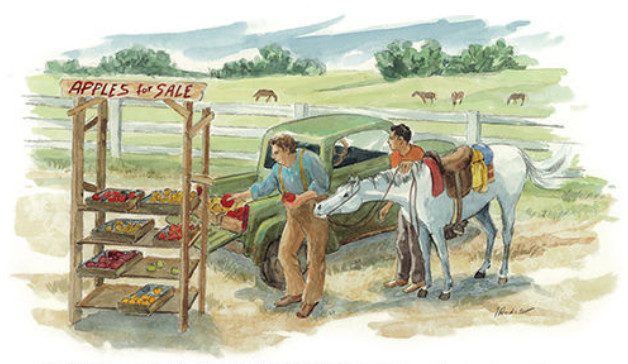

On the way through the town of Upperville, I passed an apple cart selling apples. The apple seller said: “You aren’t from around here, are you?”

On the way through the town of Upperville, I passed an apple cart selling apples. The apple seller said: “You aren’t from around here, are you?”

“No, we’re not. We’re from Arizona.”

He laughed and said in a sarcastic sort of way, “Looks like you rode from there, too.”

“Now why is that?” I asked.

“All these riders from around here ride in English saddles and look like they just came out of a magazine for some clothing company. It’s disgusting. Now you look like you’ve put some miles on that saddle, and the way you’re dressed it looks like you’re prepared to go a few miles more.”

I had on Nike 990 running shoes, with burrs in the laces probably from as far back as Texas. I wore two pairs of running tights, white over black. Holes in the white ones revealed the black tights showing through behind the knees and in the crotch. I had on white ankle socks, a purple bandanna around my wrist and another around my neck. I made quite a fashion statement!

Sea Ruler had sweat stains down all four legs to his ankles. I had been riding in some tall weeds this morning and obviously picked up some big burrs which were tangled in his mane and tail. We were a bedraggled pair and, as the man said, looked as though we had put in the miles.

I turned to him very slowly and, in a very serious and deliberate manner, said, ”We did: we rode the whole way from Arizona and we just got here today.”

He stopped laughing to see what else I was going to say. I waited about five seconds– seemed like an eternity–and then laughed and said “No, I’m just kidding. You’d have to be crazy to ride a horse that far.”

He laughed with me in agreement and said, “You’re right, damned straight, you’d have to be plumb loco to ride a horse that far. For a minute I thought you were serious.”

Washington D.C.

For most of that day I was a little preoccupied with plans for our ride through Washington D.C. and the final route to our finish. I had made several phone calls that day from the road, trying to reach Charles Applebee of the Maryland Department of Transportation. I reached the receptionist, but Applebee was still out.

For most of that day I was a little preoccupied with plans for our ride through Washington D.C. and the final route to our finish. I had made several phone calls that day from the road, trying to reach Charles Applebee of the Maryland Department of Transportation. I reached the receptionist, but Applebee was still out.

The secretary said: “Would you like to leave a message and a number where he can reach you?”

My response: “Tell him I’m the guy riding the horse across the United States and I’m 120 miles from Maryland and riding his way. I need him to clear a route for me to the beach.”

“You must be kidding.”

“No, I’m not. I’m dead serious. I need help now. We have just travelled almost 3000 miles by horseback and we only have 50 miles left to go to reach the beach.”

Maryland

Finally we’d reached the finish. We had been riding for 150 days. We’d covered 2963 miles. What could I say? It had been a monumental challenge that required every bit of mental and physical energy I could muster every minute of every day.

I had wanted it that way. I had wanted to feel the sun and the wind and the heat and the cold. I had wanted to be on the emotional and physical edge. I had asked for that challenge and I’d gotten it.

I had wanted it that way. I had wanted to feel the sun and the wind and the heat and the cold. I had wanted to be on the emotional and physical edge. I had asked for that challenge and I’d gotten it.

I wrote in my journal in Missouri: “I feel a growing burden to finish, not so much for myself, but for all those who’ve helped. We are now riding for these people. They are the real reason I keep riding.”

I continue to believe, as I did when I began this ride that the best way to convince someone you are sincere and care, is through your own example. We cared enough about this issue to take on this challenge and ultimately to finish. That is the example I wanted to set for others.